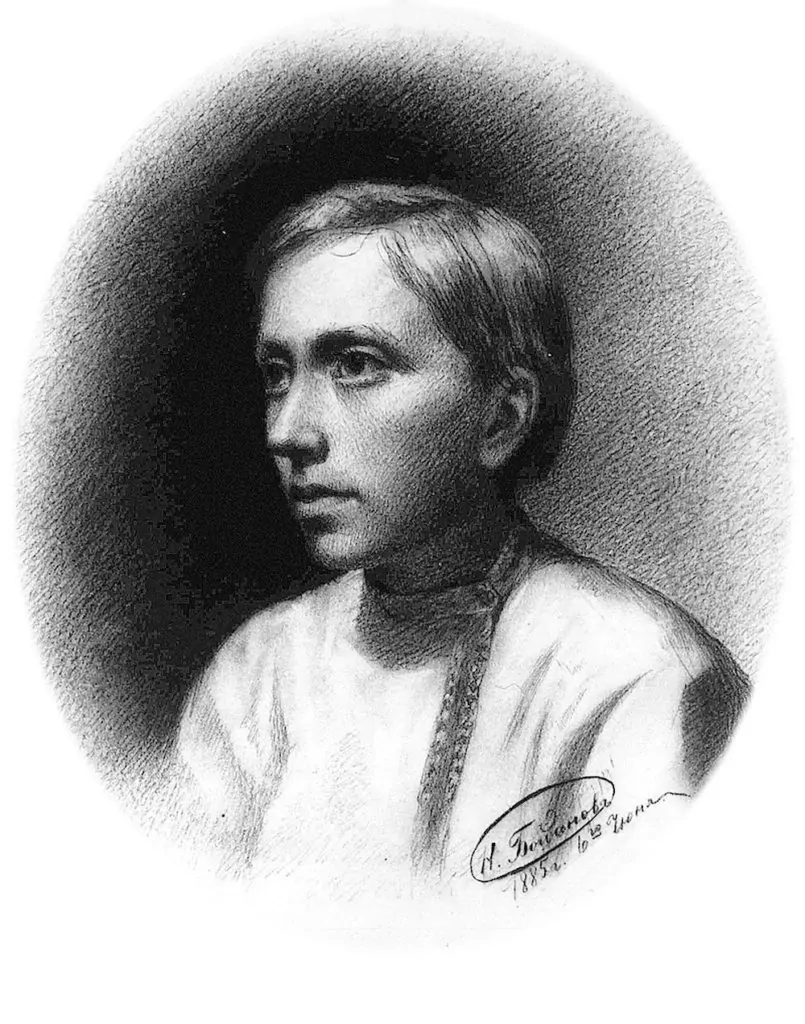

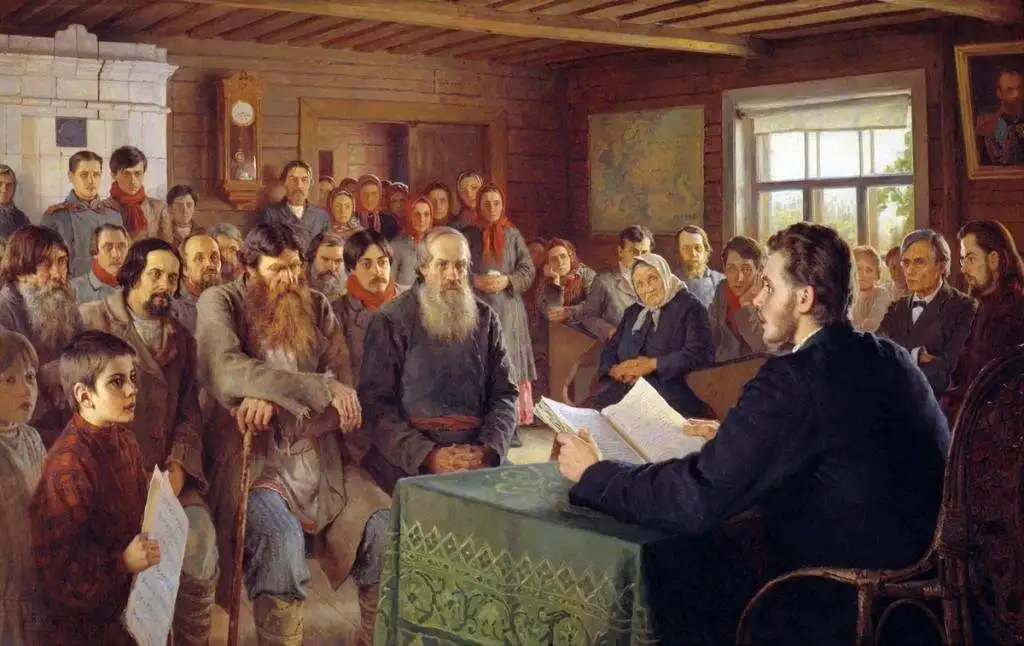

He was born on December 8, 1868, in the village of Shitiki (Шитики), in the Belsk region of the Smolensk Governorate. Because he was an illegitimate child of a peasant woman, he chose the surname Bogdanov. The second part of the surname – Belsky – comes from the name of the district in which he was born and it was added in 1905. Poor shepherd Nikolka loved to carve in wood animal figures and doodle on fences. His drawings and figurines were noticed by a professor of Moscow University, Sergey Alexandrovich Rachinsky, who at that time devoted himself to organizing schools for peasant children in his native Belsk region. Rachinsky asked the boy to paint his portrait. In the shepherd boy’s drawing he noticed an inborn artistic talent.

Professor Rachinsky took Nikolai to his school in Tatevo village. In the years 1878-1882 the boy received there his primary education. At that time, he lived in Rachinsky’s house as a member of Rachinsky’s family. At the school, children were learning religion, practicing church singing, and participating in church services. In addition, they were taught elements of grammar based on the Church Slavonic language and arithmetic based on a textbook developed by Rachinsky himself: „1001 tasks for calculations in memory”. In the botanical garden organized by Rachinsky, with rare plants brought by him from other countries, children were learning the basics of biology.

Further education of the future artist took place at the school of icon painting. Nikolka painted monks as willingly as icons. In 1884 he began studying at the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture. Rachinsky financed the entire cost of studies. The paintings of the young artist quickly attracted the attention of his teachers. He won many awards at various competitions.

Nikolai was returning to Tatevo whenever his duties allowed him to. He lived in Rachinsky’s house and painted a lot. Almost all his works between 1890 and 1900, including portraits of rural children, were created in Tatevo. Later, living in exile, he will often return in his memory to the peasant world of his native village and recreate it in his paintings.

Seeing the painting „Spruce Forest” painted by Nikolai in Tatevo, Professor Vasily Polenov said: „In your work, I am captivated by the simplicity and the inner beauty of the landscape. This forest lives, breathes – and that’s the most important thing”. Professor Isak Levitan also praised the painting, noting the special mood of Nikolai’s all works, which were included in the first exhibition of his paintings in Moscow. Five canvases were purchased for a total of 325 rubles. „Spruce Forest” was bought by Vladimir Sapozhnikov, a well-known Russian manufacturer and collector of paintings.

Starting at the age of 18, Nikolai made a living from his own work. He resigned from his scholarship of 25 rubles, which was sending him every month by Rachinsky. But Rachinsky continued to help him financially and even more with the advice and tips he was sending to Nikolai in his letters. To help the artist’s family, Rachinsky gave his khutor Davidovo, with an area of 33 tithes (about 33 ha), to Nikolai’s mother.

Future Monk (1889), one of the artist’s first serious works, has features of realism and naturalism – trends that dominated the Moscow school of painting at that time. In search of a topic, Belsky visited Tatevo. When he came to classes at Rachinsky’s school, a 14-year-old boy with pensive, sad eyes caught his attention. The boy was known for his piety. Last winter, he suddenly disappeared from the village and was found after two weeks in the forest, where he made a hut he lived. He lived on dry bread and was determined to become a hermit. He wanted to escape the world, life’s worries and joys. This story inspired Belsky to paint the picture: Future Monk. Rachinsky liked the painting, but the painter himself was dissatisfied with it. Returning to Moscow, he thought about leaving the image in the forest. On the way, there was a little accident. The sleigh fell into a snowdrift and capsized. For a moment, the artist hoped that the painting was damaged, but after a short search, he found it in the snow, intact. In 1889, Nikolai presented the work Future Monk to the examination board and received a large silver medal and the title of a professional artist.

Music has always been an integral part of daily life in Russian society. It was not only a form of entertainment but also an important element of education and upbringing. One of the recurring themes in the paintings of Bogdanov-Belsky is children playing musical instruments. Children from poor families would play the zither, balalaika, or violin, while those from wealthier families would play the piano or grand piano. The dominant form of these performances is a concert – one child plays while the audience consists of other children.

The zither, due to its simple construction and affordability, was the most accessible instrument for children from poor families. In its simplest form, it was merely a properly shaped wooden board to which 12 to 25 strings were attached. The strings were made from specially prepared and twisted animal intestines, usually sheep or goat, and sometimes horsehair.

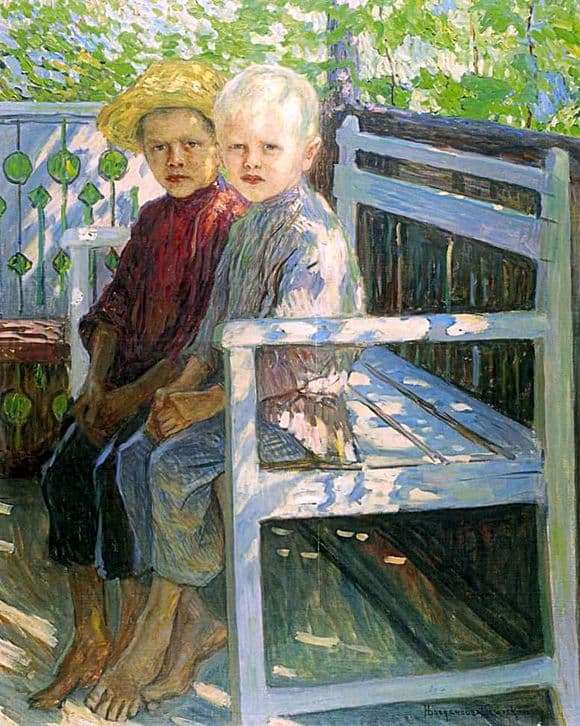

The children’s clothing is also noteworthy. Their garments are exceptionally colorful and patterned. The most expensive part of their attire was shoes. During warm seasons, almost all children went barefoot. Even in winter, not all had shoes. Often, a single pair of shoes was shared among several siblings of similar age.

In Bogdanov-Belsky’s paintings, we see that, just as today, musical culture played a special role in Russian society during his time. Russians are a nation with above-average musical talent, boasting many outstanding composers and virtuosos known worldwide for their mastery of various musical instruments, particularly the violin and piano.

In 1890, a Bessarabian (today’s Moldavia) landowner named Christie helped the budding painter pay for his journey to Constantinople and Athos. Athos is a mountainous peninsula in Greece, a place of religious worship, and a destination of pilgrimages for Orthodox believers. There are located about 20 Orthodox monasteries inhabited by monks. Belsky stayed in the hotel of The Monastery of St. Panteleimon John. During his visit to Athos, he was painting a lot, chatting with the monks, and writing down his natural observations. On Athos, he met Philip Maliawin, who had been a novice for six years and was painting icons in the monastery’s painting studio. Bielski really liked Athos. He even considered becoming a novice and icon painter like Maliawin, but fate chose a different path for him.

Belsky’s works, created before 1920, very realistically reflect the atmosphere of the last years of tsarist Russia. Thanks to the variety of topics taken up by the artist we can see the cross-section of Russian society of that period. The biggest part of Belsky’s painting legacy is devoted to peasant children. They are the main characters of his works. In them, the painter saw a hope for a better future for Russia. After the revolution, Belsky’s paintings of the poor peasants were used en masse by Soviet propaganda as an image of tsarist Russia. On the other hand, the works in which he depicted children from prosperous peasant families were hidden from the public as enemy kulak propaganda.

In 1938, the German Reich annexed Austria and the Sudetenland. At the beginning of 1939, the occupation of the entire Czech territory began, and the Klaipėda Region, which belonged to Lithuania, was forcibly incorporated into Germany. Even in Latvia, located on the periphery of Europe, where Bielski resided, the looming war could be felt. Against the backdrop of these events, the painting „Tug of War” was created.

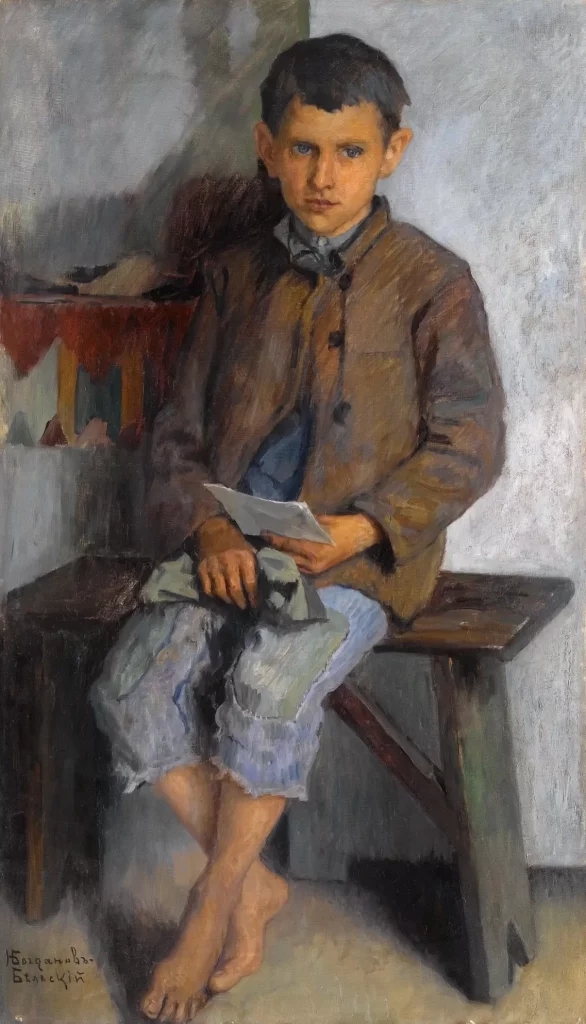

On the Threshold of the School (1897) is an autobiographical picture. The future painter, still a shepherd boy, is standing in the doorway of the classroom. There is an exam in the middle. It is necessary to draw a portrait from nature. The boy feels that this moment will decide his fate. He’s trying very hard. The drawing comes out surprisingly well. The figure in the picture is even slightly similar to the posing model. Thus, he is admitted to the primary school of Sergey Rachinsky in the village of Tatevo.

Each of Belsky’s paintings is a testimony of his times captured on canvas. With the richness of details and the range of colors, they appeal to the recipient’s imagination much more than any other form of communication. How poor is this little shepherd boy with his clothes torn and dirty! In principle, the whole of his clothes consists of patches sewn on top of each other. In many places the old material disintegrated completely, revealing naked flesh. On the feet, ragged, torn cloth wrapped around serving as socks, and crumbling straw shoes. A bag on the back. Inside, probably some provision or maybe payment for the exam? A head of cabbage? Potatoes? The second bag is slung over the shoulder. There is something in it, but what? Only the little shepherd knows.

From 1894 until 1895, Belsky lived in St. Petersburg. He studied at the local Academy of Fine Arts, in the studio of the outstanding Russian painter Ilia Repin, participated in exhibitions in Paris (1909) and Rome (1911). His works were published in many magazines, among others in Niva, Artistic Treasures of Russia, and Capital and Farm. The artist’s paintings were bought by the Tretyakov Gallery, the Russian Museum, museums in Arkhangelsk, Almaty, Nizhnetagilsk, Omsk, Samara, and many more – where we can see them to this day.

One day, Belsky received a message that Empress Maria Feodorovna expressed a desire to purchase his painting Future Monk. Unfortunately, the picture had already been sold. Rachinsky came to the aid of the former student and through a friend contacted the owner of the painting, informing him that the tsarina would be very grateful if he agreed to resell her the picture. The owner of Future Monk wrote back he would feel honored if he could give the painting to the Tsarina free of charge. That way, the picture ended up in the hands of Maria Feodorovna. Later, the former owner will admit to the artist that he missed the painting very much.

With the money received from the sale of the painting Sunday Reading in a Country School, Belsky went to Paris, where he studied painting in the studios of Fernand Cormon and Filippo Colarossi. He then traveled to Germany and Italy. In letters to his pupil, Rachinsky recommended him studying not only French painting but also Russian art, especially the works of Wiktor Wasnetsov. Around 1900 the artist stayed at the composer Artur Rubinstein’s dacha in Peterhof.

At the request of Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich Romanov, the governor of Moscow, Bogdanov-Belsky painted a portrait of Grand Duke Dmitry Pavlovich, cousin of Tsar Nicholas II. The boy was then 10 years old. The portrait of Countess Sheremeteva was another great success of the painter. Soon, Empress Maria Feodorovna commissioned a portrait of herself from Belsky. In 1903, Belsky completed his studies at the Academy of Fine Arts. In 1905 he received the title of academician and in 1914, became an ordinary member of the Academy of Arts. In the spring of 1904, Tsar Nicholas II commissioned the artist to paint his portrait.

With the Tsar Belsky met in 1906. While painting Tsar’s portrait, the artist was telling the Emperor about the life of peasant children, about their zeal for learning, about the outstanding teacher Rachinsky. The portrait was completed in 1908. The last meeting between the painter and the ruler took place at the Peterhof Palace. The Tsar shook his hand and said, „I like it very much. Thank you. I hope this painting won’t be the last.”

In the years 1913-1918, Bogdanov-Belsky was the chairman of the Society of A.I. Kuindzhi – a millionaire who entrusted all his capital to the organization in 1910. The money was used to organize exhibitions, art competitions, and fund cash prizes for the best students of the Academy of Fine Arts. During World War I, the society also helped the army.

After the October revolution, the artist took also part in a traveling exhibition in 1918 and the First National Art Exhibition in 1919.

Tea was a particularly cherished beverage in Russia. It was served during festive meals and offered to guests—both those who were warmly welcomed and those to whom special respect was to be shown. Interestingly, for a long time, tea was served in saucers, while glasses were used for compotes.

The revolutionary events in Russia in 1917 and the change of power left a profound mark on the artist’s life. He could not accept the new regime and the forced implementation of the new order. He was particularly outraged by the fact that the peasantry, which had always been the foundation of the state’s prosperity, was so thoughtlessly destroyed and deprived of land. Dispossessed peasants were forced to abandon farming and move to work in factories. In 1921, Belsky left Soviet Russia and moved to Riga at the invitation of his friend and fellow artist, Sergey Vinogradov. He spent the next 20 years of his life in Latvia.

In Riga, Belsky’s works enjoyed no less recognition than in Russia, and the artist struggled to keep up with commissions. Between 1921 and 1922, a solo exhibition of his works was organized at the Riga Art Museum. Many paintings were purchased directly from the exhibition for private collections. To this day, it is unknown whether these works still exist or who their owners might be.

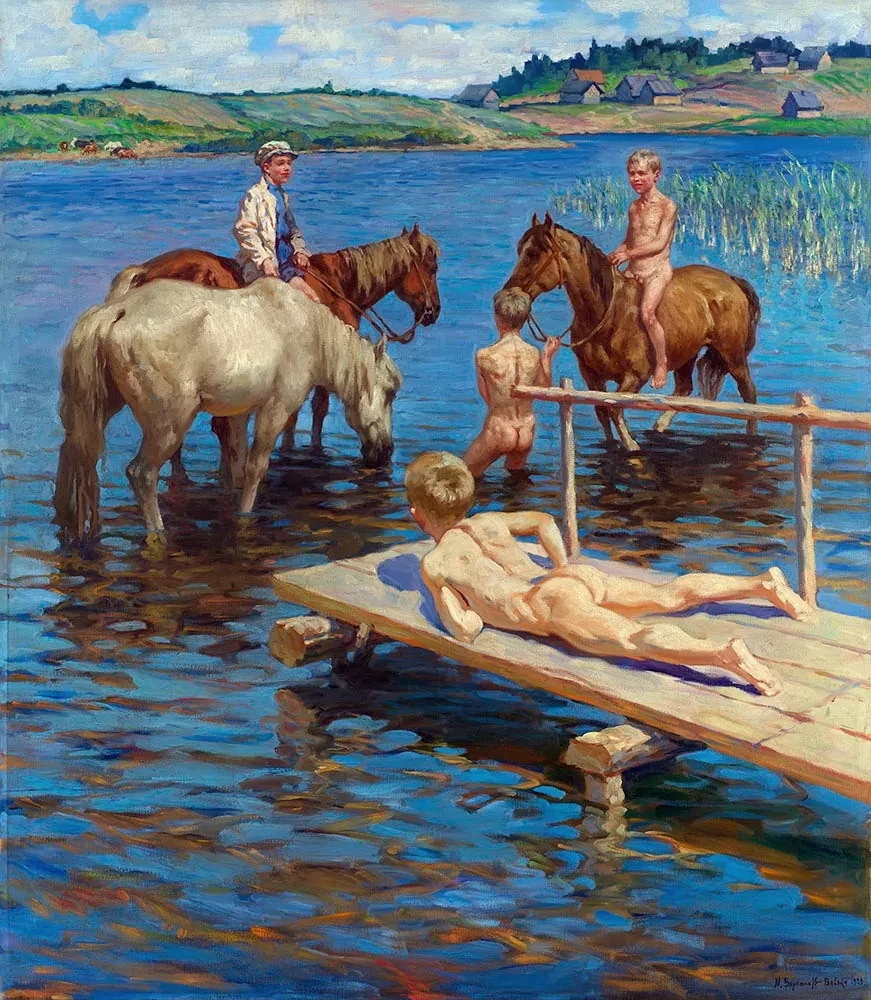

The painting Bathing Horses was created in 1929. It is the only canvas in which one of the figures—the boy lying on the pier—was directly “borrowed” by Bogdanov-Belsky from a painting by another famous artist, the Spaniard Joaquín Sorolla. This gesture can be interpreted as the artist’s expression of admiration for Sorolla’s work and, at the same time, a statement of artistic and spiritual connection with the Spanish painter, who also devoted a significant part of his art to children.

It was Sorolla’s series of paintings depicting children playing on the beaches of Valencia, created in the early 20th century, that brought him the greatest acclaim and fame. Bogdanov-Belsky’s Bathing Horses was painted about 20 years later when Sorolla’s artistic reputation was already well-established in Europe. However, the two artists shared more than just a passion for painting.

Bogdanov-Belsky was the illegitimate child of a poor peasant woman and was raised by an unrelated but exceptionally kind family, the Raczynskis. He never learned the identity of his biological father. Joaquín Sorolla’s childhood was no less tumultuous. Before he turned two, he lost both his parents to an epidemic. Together with his sister Eugenia, he was taken in by their maternal aunt and her modest family, who made a living through the locksmithing trade of her husband. These similar childhood traumas shaped the sensitivity of both artists and their deep empathy for children.

Living in Latvia, the summertime Belsky was usually spending in Latgale. Latgale is the eastern part of Latvia, full of wild forests and lakes. He was staying at the estate of the daughter of the writer Aleksandr Zhemchuzhnikov. It was there where the series of paintings, Children of Latgale, was created. Apart from this, lots of Latvian landscapes and still lives. The situation in Russia, as before, bothered the artist. In 1924, he painted the picture „Former Defender of the Fatherland” The canvas depicts the Russian army officer who, having lost his homeland and the opportunity to serve the tsar, lost the meaning of life. Under a dim lantern, he sells newspapers on the street in Riga and reads the latest news about events in the world over which he no longer has any influence.

At the first Soviet Painting exposition in America held in 1924, Bogdanov-Belsky exhibited more than ten of his works. The exhibition enjoyed a lot of interest. Russian paintings were of great interest also at the grand exhibit in Prague in 1928. In Prague, collectors bought ten works by Belsky. The National Gallery in Prague also purchased one of his pictures. At the display of Russian paintings in Copenhagen in 1929, the entire first room was devoted to Belsky’s works.

It was not only exhibitions that made Belsky a painter recognized all over the world. The newspapers of the time widely printed reproductions of his works, thanks to which his name had a chance to penetrate the consciousness of the educated middle class.

In Riga, Belsky worked intensively, but was also deeply involved in the social life of the Russian community. He was a member of the council of the Russian Drama Theater and the Russian Club, one of the organizers of the Literary and Theater Society, a member of the Hunting Society, a member of the Circle of Lovers of Russian Antiques.

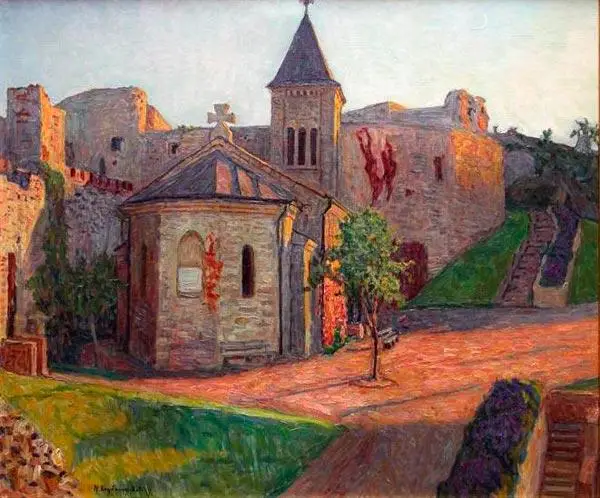

In the autumn of 1935, the Serbian Patriarch Varnava (a graduate of the St. Petersburg Theological Academy) asked Belsky to paint his portrait. The artist traveled to Belgrade and then to Dubrovnik. In addition to the commissioned portrait, he painted some landscapes: the Russian Church in Raguza (Raguza, Rakusa – the old name of Dubrovnik), the Old Gate of Raguza, Way of St. James in Ragusa.

In April 1941, Belsky’s painting „A shepherd boy Proshka” (1939) was presented at an exhibition in Moscow. It was the Master’s last exhibition during his lifetime.

From his first wife, Natalia Antonovna, Belsky separated in 1921 after more than ten years of marriage. Her image was preserved in several paintings, including: „A sick teacher” and „Teacher’s name day” The second companion of the artist’s life, until the end of his days, was Antonina Maksymilianowna Erchard – of German origin. Their letter romance lasted from 1922, but it was not until January 1932 that they were married in the Orthodox Church of the Nativity in Riga.

At the end of war, the artist’s wife took him to a well-known Berlin clinic for an operation. Nikolai Bogdanov-Belsky died on February 19, 1945, during the bombing of Berlin. He was buried in Berlin at the Tegel Russian Orthodox Cemetery.

For many years, Soviet Russia tried to erase the memory of Belsky, treating him as a traitor and a class enemy. At the end of his life, when the Second World War was sweeping across Europe, Belsky painted several portraits of German generals as well as a portrait of Hitler, which after the war sealed his status as a „traitor to the nation” in Soviet Russia. After all, let’s remember that the artist’s wife was German, Latvia during WW II was an ally of Germany, and the artist, although of peasant origin, was treated in bourgeois, international circles almost like an aristocrat. Probably Bogdanov-Belsky was a Hitler sympathizer because only Hitler’s victory could give Russia a chance for recreating in the shape Belsky dreamed of.