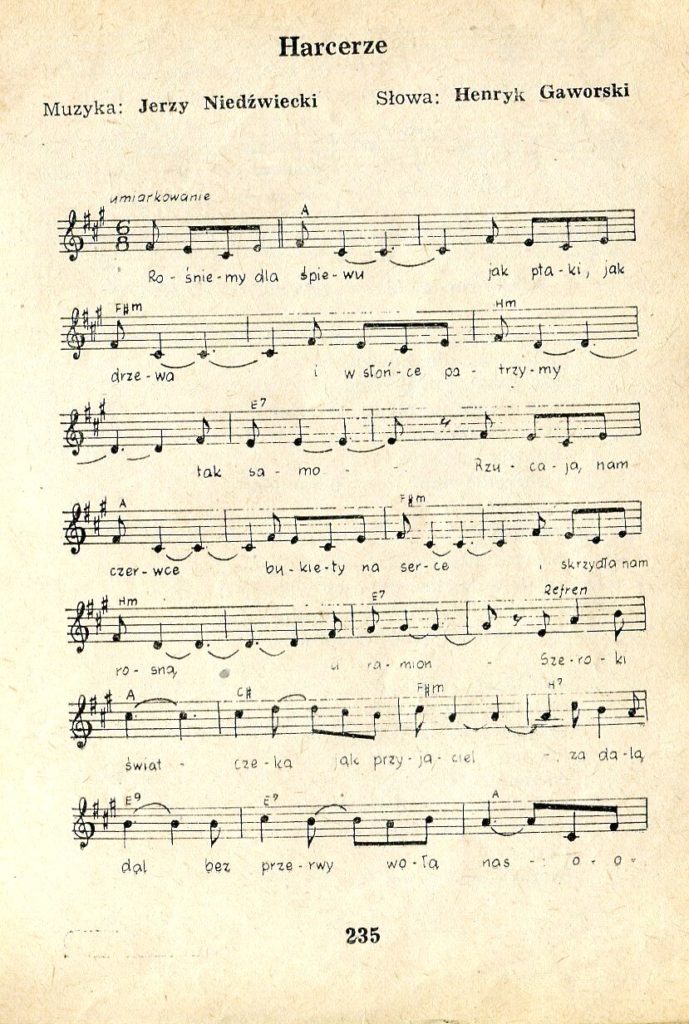

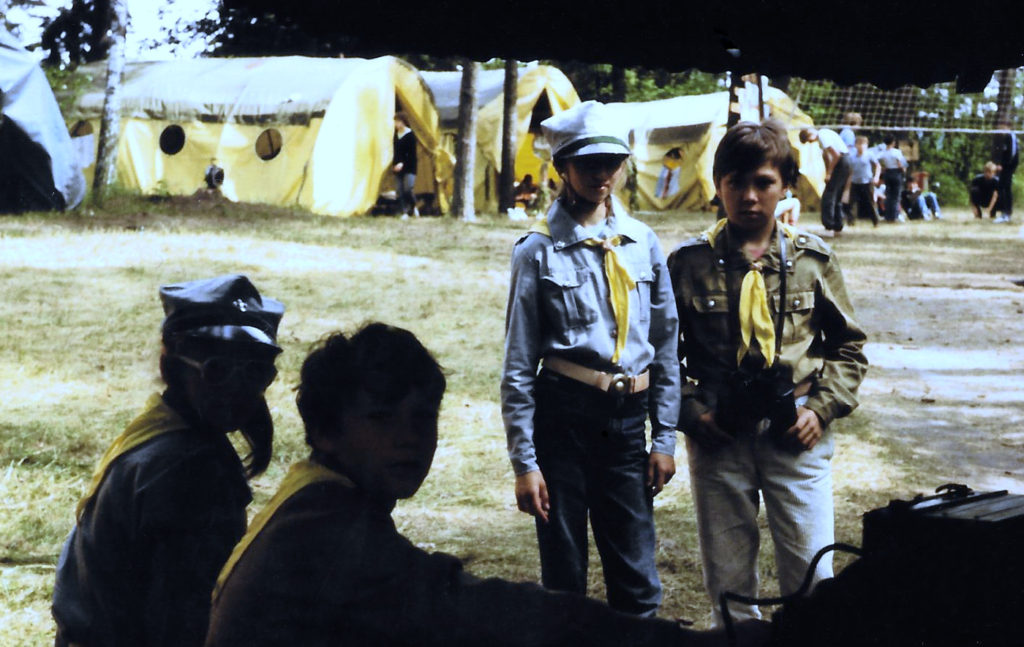

When dusting bookshelves in your home library, sooner or later, you must end up with a sentimental journey into your childhood. How could it be any different when your gaze falls upon an old scout songbook, a relic rarely utilized in modern times? Despite its slight wear and tear, the songbook itself is not that ancient, having been published in 1983. Nevertheless, many of the songs it contains trace their origins back to the ’70s and even the ’60s. The patriotic part, once fervently sung, have undeniably become relics of a bygone era, reminiscent of the now-defunct People’s Republic of Poland. However, certain melodies within its pages have defied the passage of time. Can songs that extol friendship, brotherhood, the splendor of nature, or the enchanting ambiance of a campfire truly grow old? I think not. These timeless tunes evoke emotions that transcend the boundaries of time and place. As I leaf through the worn pages, memories flood my mind, transporting me to the innocence and camaraderie of scouting adventures long past. The melodies echo the laughter shared with fellow scouts, the bonds forged around crackling fires, and the awe-inspiring beauty of the natural world that surrounded us.

The scout camp I used to attend as a boy was organized every summer on the shores of Białe Lake near the small town of Włodawa, right on the Polish border with Belarus. In those days, it was a completely untouched place, hidden behind seven mountains and seven forests. To the northwest, farmland extended up to the edge of the lakeside reeds. Towards the west, the fields turned into a vast wasteland, sparsely covered with young trees. It was on this wasteland that our camp used to stand. From the south, a pine forest approached the lake’s shoreline, with a few sleepy recreation centers nestled among the old trees. These centers usually appeared abandoned, as if no one resided there. The lake was surrounded by forests on its east, west, and southern sides. I knew it was sizable, but I never truly grasped its immense scale.

The most stunning beaches stretched along the northeastern and eastern shores of the lake. The sand meandered deep into the water, which shimmered with a greenish hue. The clarity was such that even at a depth of 3 meters, one could still see the sandy bottom. Several piers divided the bathing areas from the deeper waters, some extending far into the lake where the bottom was no longer visible. This earthly paradise remained largely empty and undiscovered. Only on Sundays did the typically quiet village of Okuninka, which bordered the northeastern shore, come alive as residents from nearby Włodawa town sought relaxation there.

Frequently, we ventured into the forest alone, without any adults accompanying us. Individual scouts were not allowed to leave the camp, but as a group, we had the freedom to explore. It was sufficient to inform our scout team leader and obtain permission. In the forest, we gathered wood for evening bonfires, picked chanterelles and blueberries for our meals, or played various strategic games. All of this took place in a wilderness teeming with reptiles and wetlands, spanning across many kilometers. The branches we collected from the forest were cut into smaller pieces, some destined for the campfire and others for the needs of our field kitchen.

Thicker stumps and tree branches were cut into smaller pieces using hand saws and then chopped with an axe. Boys as young as ten years old (or even younger) handled sharp axes with no less skill than a football on the school field. This was an unremarkable sight, evoking neither surprise nor admiration. Every scout wore a finka on their belt – a more or less sharp scout knife. It was useful for cutting branches but ill-suited for peeling potatoes. Each team had kitchen duty once a week, and then was responsible for peeling potatoes for the entire camp, filling the field kitchen’s tanks with drinking water, cleaning the kitchen after meals, and assisting the cooks throughout the day. Some food items, such as mushrooms and berries, were gathered from the nearby forest. There was an abundance of mushrooms and berries. I liked collecting chanterelle mushrooms the most. It was enough to walk along the forest path a bit deeper into the forest and right under your feet yellow clusters of chanterelles, visible from afar, began to appear. The further you went into the forest, the more of them there were. At one point, the entire path seemed to shimmer with yellow spots. We could gather them in buckets, just like the berries, although chanterelles were harvested much faster.

The most troublesome aspect of this wild wilderness was the presence of mosquitoes. At first glance, our chances of winning the battle for our blood seemed slim. The enemy army held a significant tactical advantage and outnumbered us by a considerable margin. As we sat by the fire, we would sometimes wonder how many mosquitoes lived in a forest like ours. Unfortunately, even a perfect knowledge of the multiplication table was insufficient for a rough estimate. However, we had an effective method to combat them. It involved a plant with an incredibly potent, balsamic scent known as the „swamp.” In the wet parts of the forest it grew massively, creating extensive, intensely green carpets, up to one meter high. It wasn’t difficult to find it. On hot days, the number of essential oils secreted by it was so large that it was enough to enter the forest and follow the odour to find its nearest location. In areas where the „swamp” grew, insects were nearly absent as the plant’s intense aroma effectively repelled them. Bringing a bundle of its twigs into the tent was effectively deterring mosquitoes from entering for some time, and fumigating the tent with smoldering twigs of the „swamp” yielded even better results. We would also fumigate our clothes, and it worked probably more effectively than most of today’s specifics against mosquitoes. The only downside to our mosquito repellent was that the plant’s caustic essential oils required careful handling. Scouts who were careless could end up with an itchy rash on their skin. Ticks, on the other hand, seemed to be non-existent during those times. I don’t recall anyone having to remove a tick. However, there was no shortage of worms, grass snakes, and zig-zag vipers. We slept in 14-person tents on sturdy wooden beds with firm mattresses.

Due to the moisture-laden air, our bedding, consisting of a thick blanket in a duvet cover and a gray sheet on the mattress, was always slightly damp. Every morning, the first task upon waking up was to shoo away any amphibians or reptiles that had found their way into the tent. After a rainy night, they would be particularly abundant. Sometimes, it would be a grass snake, and other times, a zig-zag viper. The forest paths were teeming with them, as the surrounding forests were waterlogged and filled with marshes and quagmires – an ideal habitat for all reptilian creatures. Interestingly, no one was ever bitten by a viper. Among the reptiles, my favorite were the large green lizards. On sunny days, they basked on stones and sandy forest bald spots. They were almost completely unafraid. It was easy to catch, and even tame them.

We were constantly reminded of the biggest threat, which was not the zig-zag adders we encountered almost daily or the giant elks lazily roaming the forest. It was a tiny larva, a developmental stage of a fluke that cause a dangerous parasitic disease known as fasciolosis. This disease primarily affects cattle and forest animals, but it can also result in fatalities among infected humans. The parasite eggs pass through the host’s digestive tract and are excreted through feces. If these eggs find their way into a water reservoir, they can develop into larvae that invade the bodies of aquatic snails. Within the snails, the larvae undergo transformation and multiplication. Once they left the snail’s body, most often the marsh harrier, their spore forms float freely in the water or attach themselves to the stems of coastal plants.

Infection with the parasite occurre when one drank contaminated water or inadvertently transferred the spores to the mouth through dirty hands. The flukes primarily attack the liver but can also infiltrate other organs such as the eyeball, brain, or heart. Because water snails love small and muddy water reservoirs, with stagnant, warm water, and at the same time, such reservoirs often serve as watering holes for animals, the probability of catching fasciolosis there is extremely high. Fully aware of this danger, we never entered these waters, avoided washing our hands in them, and refrained from using them for any other purposes.

Once a week, there was a communal bath – one day boys, the next one girls. On boys’ bath day, the girls would venture into the forest to gather mushrooms or berries, and vice versa. The water for bathing was heated in our camp’s field kitchen. On these special days, meals were slightly more modest, such as enjoying blueberries with cream or savoring chanterelle sauce with pasta (which was absolutely delicious). From the crack of dawn, the field kitchen buzzed with activity as water was heated with fervor. The bathing ritual took place in a large tent that doubled as a storage area for various camp supplies. On bath days, the tent would be cleared out and transformed into a makeshift bathhouse. But in practice, everything would happen outside of it. We ingeniously utilized garden watering cans as makeshift showers. The bath required close cooperation. When one boy, standing on a stool, was holding a watering can and acting as a voice-controlled shower, the other was soaping and washing. As expected, the initial order planned by the adults swiftly dissolved into cheerful chaos. Once shyness was overcome, naked boys would playfully chase one another around the tent, gleefully drenching each other with water using watering cans and buckets. Shortly after, the fun was moving to the territory of the entire camp. When the supply of hot water ran out the buckets were filled with water from the nearby lake. Only the sheer physical exhaustion of the boys could restore a semblance of order to the camp. The group that had just enjoyed their bath would then shoulder the responsibility of fetching water and heating it in the camp kitchen for the next teams. In today’s world, it’s likely that the entire adult staff of our camp would be accused of violating numerous sections of the penal code. What a fortunate that my childhood occurred in an era when when the most important of the pedagogical wisdoms sounded, 'From time to time give him some food’.

Late in the evening, as darkness fell, our team would sneak out of the camp to go for a swim in the lake. We were often joined by a few friendly boys from other teams. Instead of using the designated bathing area in the camp, we would walk a little further along the shore to a secluded sandbank hidden among the reeds. Our scout team leader, a young man in his early 20s, would accompany us. This whole excursion was conducted in secret, a small act of rebellion against the camp rules that prohibited leaving the camp area after 9 pm.

While swimming, we were instructed to stay close to the shore and remain visible for team leader. Some of the boys chose to bathe naked, while others wore underpants. Each person decided for themselves how they wanted to enjoy the water, although it was widely agreed that naked bathing was much more enjoyable. Returning to the camp, we would slip into tent as quietly as we had left. Usually, no one would notice our half-hour absence, or perhaps no one cared to notice. Those who wished to do so could go straight to bed. The official night silence began at 10 pm, but most of the boys would only enter their tents briefly to grab their warm blankets before heading towards the bonfire. There, we would sing scout songs late into the night, enjoying the camaraderie and the warmth of the fire.

During a trip to nearby Włodawa, the leader of our scout team asked, „Who wants to see what an Orthodox church looks like inside?” Several scouts, including myself, eagerly responded. As we approached the place, the church gradually emerged from the lush greenery of the surrounding trees. A narrow alley, adorned with chestnut trees, led us towards it. Compared to Catholic churches, it appeared rather small. Just beyond the church courtyard, the land gently sloped down towards the Bug River, revealing a breathtaking view of Belarus on the other river side. Only from the riverbank could the church be fully appreciated in all its glory. Bathed in the rays of the afternoon sun, it appeared as if it had been plucked straight from a fairy tale. Its domes shimmered with gold, while the walls radiated in white and blue hues.

We stepped inside, and I held my breath in awe. I didn’t know where to direct my gaze; everything felt so new and different from the church I usually attended. The service was in progress, accompanied by resounding choral singing that seemed to emanate from all directions. I strained to catch sight of the angelic voices, but the choir remained hidden somewhere deep behind the altar. Oh, how they sang! It sent shivers down my spine. On one side, resonant bass voices reverberated, while on the other, women’s altos blended harmoniously. It was as if I was witnessing a celestial conversation or a heavenly melody. The music’s harmony and joy captivated me, anchoring me to where I stood. Afraid of disrupting the enchanting sounds that surrounded me, I dared not move. It was an experience far removed from the somber chants heard in the Catholic church. That day, I fell in love with Orthodox music.

Years later, upon revisiting Włodawa, I found the church closed for renovation. The peeling plaster and walls covered in scaffolding left an unpleasant impression. Seeking information, I approached an elderly man I encountered in front of the church and inquired about the choir.

„Do they still sing?” I asked with curiosity. He simply waved his hand in resignation and replied, „Nobody sings like that anymore. The elderly have passed away, and the youth have moved on. The rest simply don’t have the time.”

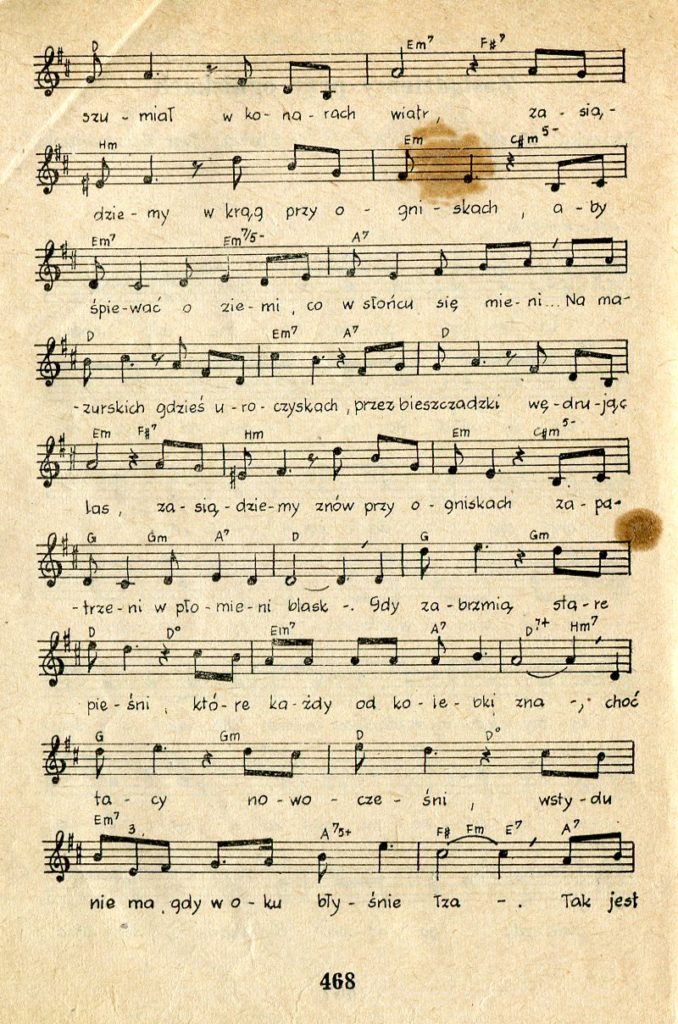

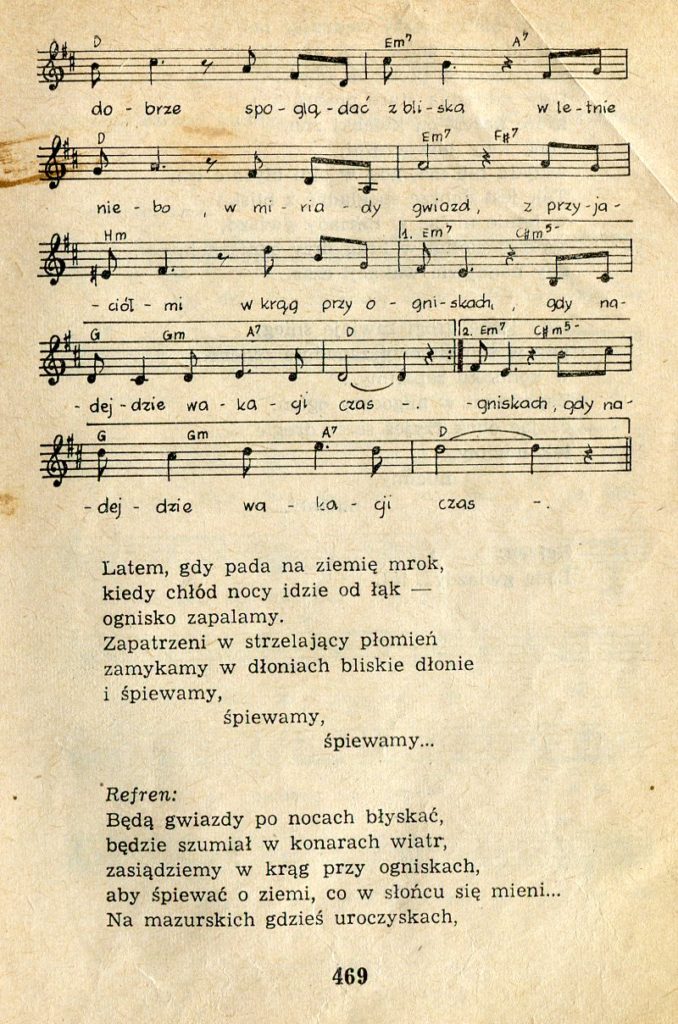

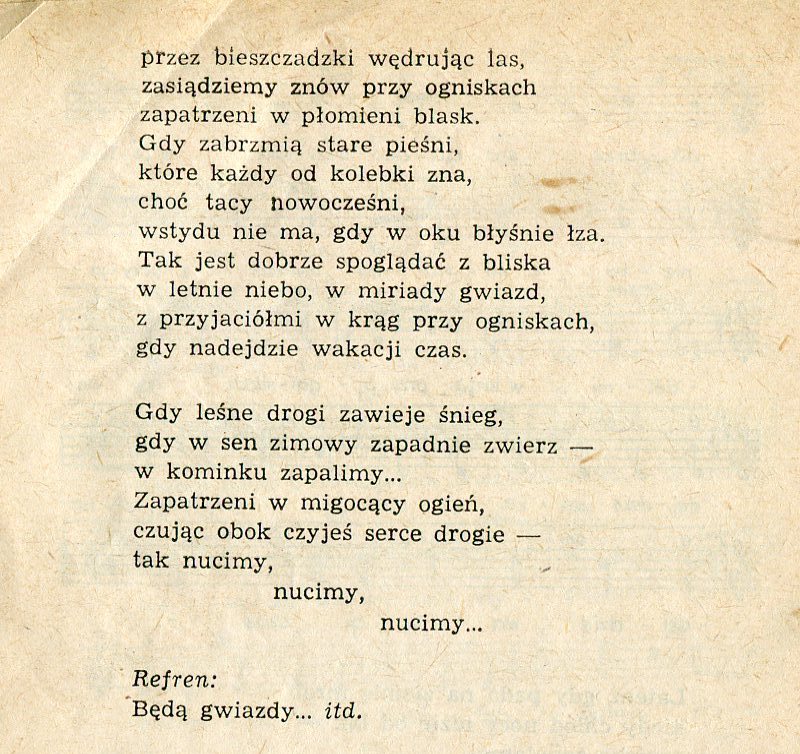

The most enchanting aspect of our summer camps was the evening bonfires. The bonfire served as a theater of light and darkness, heat and cold, possessing the extraordinary ability to bring people together and forge connections among those gathered in its circle. Even in moments of silence, when only the crackling of burning wood could be heard, the bonfire held a special allure.

Every evening in our camp, a fire would burn, welcoming anyone who wished to join. Usually, someone would strum a guitar and hum a song, and the rest of us would join in. Twice a week, a grand bonfire was organized for the entire camp, featuring a scout song competition. Each team showcased their vocal talents and prepared repertoire. Almost every team had someone who could play the guitar, to varying degrees of skill. As a last resort, the accompaniment section could be borrowed from another team or one could take the risk of a solo performance. Of course, the girls’ teams often outshined the boys’ teams in terms of singing abilities. The older boys, who were going through their awkward stage of vocal changes, often preferred to avoid showcasing their current abilities.

Certain songs were sung by the entire camp together. The bonfire’s official conclusion would not be complete without singing the familiar and obligatory anthem: „The bonfire is already dying out. Let’s form a brotherly circle. In the evening stillness, under the starlight, let’s exchange our final handshakes.” Another popular song that was always a hit at every bonfire was: „The bonfire is burning, the woods are resounding, the team leader is among us.”

Even after the official end of the bonfire, not everyone would retire to their tents. Some scouts would linger, the melodies lingering in the night air. Some would sing, while others listened attentively, their gaze fixed on the fading embers. Eventually, fatigue would take hold. The group surrounding the fire would gradually diminish, until only the night watch remained, keeping a solitary vigil.

„Harcerze”, Our songs, selection and arrangement by Jerzy Niedźwiecki

A modern map of the area of Białe Lake with the marked place where our camp stood.